With the armistice ending the First World War, signed November 11, 1918, manufacturing demand fell and unemployment swelled. Social pressures already exacerbated by wartime labor practices, inflation and postwar corporate repression of unions, only deepened as economic activity slowed. The largely eastern and southern European workforce that occupied the lower half of the mill wage scale was unionizing, but also feeling pressure from a massive injection of black labor brought from the south by the steel corporations to work if there was a strike. As the boll weevil infested cotton crops threatened agricultural life in the south, northern manufacturing was booming after 1914 with massive war contracts from England, France and Germany. Reduction of the flow of cheap central and southern European labor caused US Steel to facilitate recruitment, transportation and barracks housing for black labor.

The steel mills imposed a twelve-hour day of physical labor in a heavily polluted and dangerous workplace over an unrelenting seven-day week. Key to the social control and assault on the lives and bodies of workers imposed after the Homestead strike was the swing-shift where after seven 12-hour turns on daylight shift, you worked seven 12-hour night shifts. This led to the notorious “long-turn” of 24 hours and one full day off every fortnight (fourteen days). Workers fought for a reduction of hours with maintenance of pay, health and safety improvements, and an organized voice on the job. The organization of steel was attempted with a craft-based model of organization that divided and confused the effort. Labor activism was driven from below and expressed itself in various craft unionist, socialist, anarchist and communist organizations. Socialist Eugene Debs was a major vote-getter for president in the local industrial towns in 1908 and 1912.

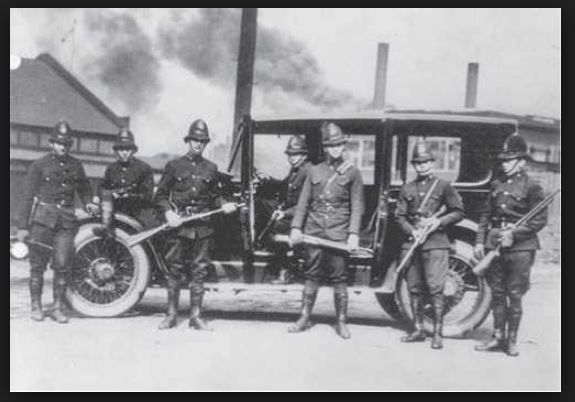

State troopers armed and ready to quell rioters during the Steel Strike of 1919 in Farrell, Pennsylvania (Library of Congress)

Preparing for the strike, US Steel was estimated to control up to 25,000 armed men in the Mon Valley. Mill management, professionals and merchants were deputized. The press almost unanimously fed a hunger for anti-foreign feelings and anti-red propaganda. The recent Bolshevik revolution in Russia shook the wealthy and powerful of all industrial nations. Strikes were going on all over the country, general strikes on the west coast, meatpackers and others in the Midwest, with hundreds of points of conflict in the coal mining and coke furnace workers of Frick and Mellon in the region surrounding Pittsburgh – largely unionized during the war but under vicious attack in 1919. A bitter trolley strike in Pittsburgh was disrupting the city’s operations. Racial tensions were on the rise with a violent summertime riot in Chicago.

The “Great (Hunky) Steel Strike” started in late September. Mother Jones was arrested in Homestead for the crime of free speech on August 25 and left Pittsburgh before the assassination of Fannie Sellins, her union sister organizer, friend and expected younger replacement for the role of female, motherly, hell raiser organizer that Mother Jones performed for the United Mine Workers. Mother Jones’ claimed an age of 89 years at the time of the strike while Fannie was more than thirty years younger, herself a formidable organizer and orator like her mentor. Fannie was murdered on a picket line in Natrona Heights on August 26, 1919 and the BHF will commemorate a life committed to the cause of labor on the centennial of her death this year.

Religious congregations played a key role in the strike and its aftermath. Fr. Kacincy’s Slovak Church of St. Michaels (now Good Shepherd) across Braddock Avenue from the mill and today’s steelworker local union hall was the only public meeting place open to strikers. However, public outrage over brutal conditions in the mills and the complete suppression of civil liberties and free speech was fueled by two influential reports by the Interchurch World Movement (later the mainline Protestant World Council of Churches). By the mid-1920s, US Steel and others were pressured to adopt a three-shift seven day system with a 56 hours week.

While reform came slowly and unionization in steel was only achieved in 1937, the expulsion of “foreign agitators,” particularly anarchists and communists was carried out by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer on January 2, 1920. J. Edgar Hoover used these raids to build his fledgling FBI. The Ku Klux Klan raised its ugly head in the early 1920s as an organization that attacked both blacks and Catholics.

The story of 1919 concerns massive immigration to feed rapid industrial growth followed by government-sponsored hysteria against foreigners and radicals in the name of Americanism; the cynical manipulation of white racism in response to black migration from the South; and direct corporate manipulation of public opinion and the press. Workers fought for decent wages, a restriction of the hours of work, health and safety standards, and representation on the job. The legacy of the strike included a deep racial divide in the steel towns, but also a widespread realization among workers that large corporate industries could only be organized through an industrial union structure. The 1919 strikes were defeated but still made important gains and prepared workers for the upsurge of union organization in the 1930s. ~ by Charles McCollester

0 Comments