“Consequences of the 1892 Battle of Homestead”

Remarks presented July 6, 2023 at The Pump House by Charles McCollester, Ph.D.

______________________

Carnegie Steel blast furnace, Homestead, 1902

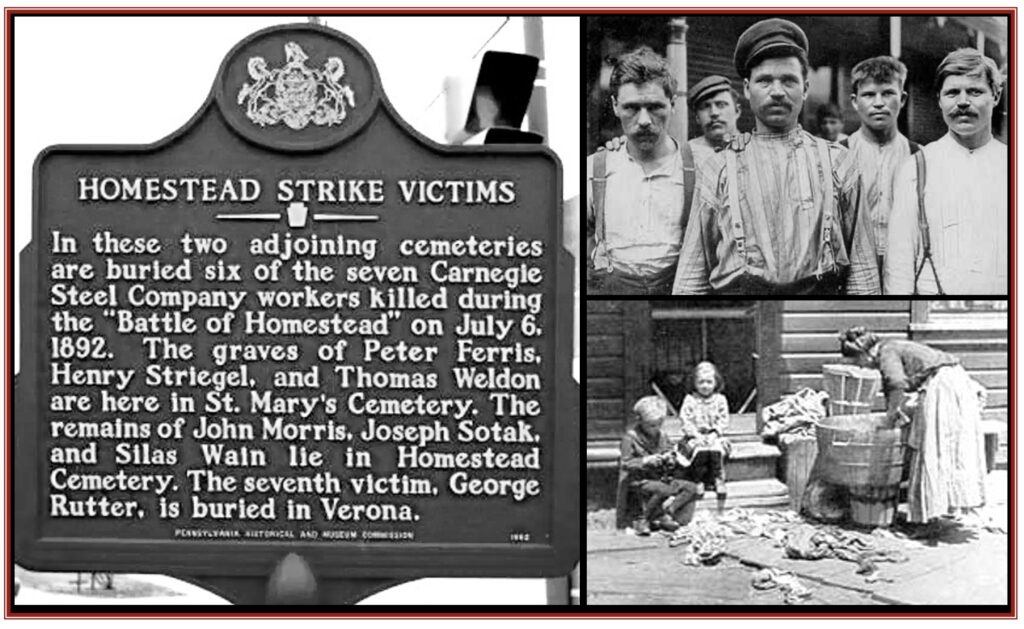

OVER THE PAST 31 years, we have gathered many times at the site of the dramatic events of July 6, 1892, to remember industrial workers’ resistance to the forceful imposition of unchecked corporate rule in the workplace and over their community by a combination of hired guns, the blacklist, company spies and state power.

The dramatic gun battle, the gauntlet that expressed the outrage of a community, the military occupation of the town, was witnessed by thousands of spectators, and widely reported at home and abroad.

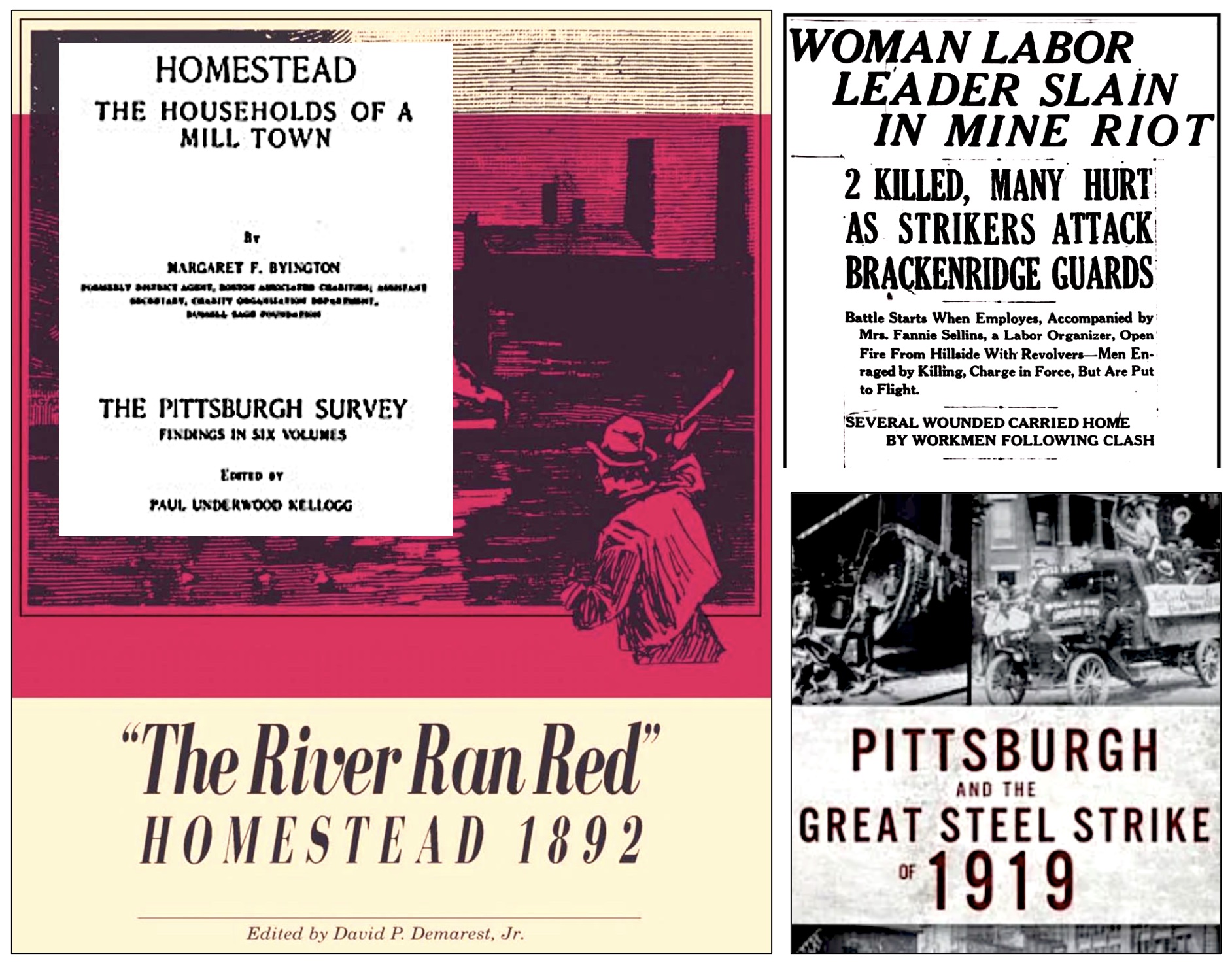

The July 6 story is told in dozens of books and films with another major film on the way.

We live still in capitalism’s dark, polluted shadow.

We live still in the shadow of Homestead 1892.

The historic significance of the battle is linked to two aggressive and ambitious men, Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, founders and shapers of a revolutionary and ruthless capitalist industrial order that achieved global dominance.

Such attention to the story of July 6 masks the deeper significance of the breaking of union organization and the suppression of political participation. The principle asserted at Homestead was employment at will, unchecked company control over a worker’s livelihood, a control buttressed and extended through domination of the community.

To grasp the significance of Homestead 1892, one needs to understand the heights, the hope, the creative possibilities for a cooperative commonwealth that were blocked when the “Workers’ Republic” that existed for three years under the union contract was crushed and replaced by a system of total corporate control.

There are three parts to the story:

PART ONE: The Workers’ Republic

Voice in production. Under the union contract in force from 1889 to 1892, the union exercised significant shop floor presence as management’s operation and plans were constantly questioned by “busybodies from the Amalgamated”. Issues of safety, manpower and pay were subject to constant negotiation. Private property was challenged by concerted activity. Shopfloor engagement by workers particularly infuriated H.C. Frick.

Pay. During these three years (1889-1892) there is constant and intense negotiations over compensation. In the iron industry, pay was based on productivity – workers’ wages were directly linked to metal produced. Carnegie was determined to break this ancient linkage as steel productivity soared. He demanded wages be tied to the price of metal which was dramatically falling.

Hours of Work. Under the union contract most workers worked between 50 to 65 hours a week with virtually everyone except furnace tenders free on Sunday. Men worked straight shifts allowing for family life and civic engagement.

Community Democracy. In Homestead, workers dominated politics. Union members formed a strong majority on the local Council, and the mayor, “Honest John” Mcluckie, was an eloquent voice in opposition to corporate control.

Ethnic Solidarity. The second and third generation Irish leadership of the Amalgamated Association lodges formed close alliance with the unskilled labor force of mostly Eastern Europeans. Many Slavs had close ties to the coke ovens and mines of H.C. Frick. With the Mammoth Mine Explosion and the Morewood Massacre occurring in 1891, they knew and distrusted Frick’s intentions.

PART TWO: Corporate Dictatorship, 1892-1937

Hours of Work. Drastic increase in the length of the workday. A two-shift, 84-hour week is imposed on the lower 60% of the workforce. Sunday is just another day of work.

Pay. Despite radically increased hours, total pay for most workers substantially decreases. Any link between productivity and pay is severed.

Absolute Employment at Will. Union workers are blacklisted in the industry. An extensive system of company spies ensures that dissidents are fired. While high union wages pushed Carnegie toward constant innovation to reduce labor costs, the suppression of worker participation and the downgrading of workers’ skills leads to an oligarchic, conservative industry that stagnates. The American Steel Industry dies slowly from the head down.

Suppression of Democratic Participation. Following the strike, electrification allows mills to run 24-7. Imposition of two 12-hour shifts, combined with the brutal “swing shift” creates the notorious “long turn” of 24 hours work every two weeks. The corporation thus completely severs most workers from the civic and political life of the community.

Extreme Inequality of Wealth and Sacrifice. While industrial workers’ wages are drastically reduced, capitalist wealth and power increases geometrically. Workers are literally worked to death with many being killed or maimed on the job. Enormous concentration of wealth distorts national values and corrupts government at all levels.

Fomenting of Racial Division. In the 1919 Steel Strike, when Eastern and Southern European rise up to challenge this brutal system, US Steel massively imported Southern Blacks to break the strike. Black workers desperate for economic opportunity were pitted against Slavic immigrants struggling to survive.

PART THREE: Industrial Citizenship, 1937-1986

“When Democracy was more than just words”

1937 SWOC. The union upsurge of the 1930s established industrial citizenship for Homestead Steelworkers. This provided protection of employment, limitations on hours, the right to speak and to negotiate wages and working conditions. Union political candidates swept working-class communities challenging corporate control of police and judiciary. Prosperity came to Homestead town.

1959 Steel Strike. The key issue in the 1959 strike was workers’ right to challenge management decisions on the shop floor when they undermined past practice and existing agreements. Rank-and-File insurgencies like the “dues rebels” prepared the ground for the subsequent insurgent run of Ed Sadlowski for USW president in 1977.

1978: Local 1397 Rank-and-File. The victory of a radical USW reform slate at Homestead coincides with corporate America’s decision to abandon American manufacturing, its workers and their communities. Corporations, with the connivance of government, adopt an imperial strategy based on cheap imports from politically dependent countries. This strategy enormously enriches coastal elites while closing thousands of productive enterprises and devastating many thousands of established communities in the American heartland.

Like the militant unionists of the 1889-1892 Workers’ Republic, Local 1397 (under the leadership of Ron Weisen, Mike Stout, Michelle McMills et al.) builds a strong internal organization that constantly challenges management on the shopfloor. 1397 joins with UE 610 and other unions in 1986 to organize a Steel Valley Authority, joining the City of Pittsburgh with seven Mon Valley communities, to challenge corporate abandonment with the power of eminent domain. At the end as at the beginning, Homestead asserts people’s right to have a meaningful voice concerning the terms and future of their employment.

The “Mon Valley Insurgency” growing directly out of Youngstown’s resistance to capitalist disinvestment asserts that communities have a “certain property right” to the places of their work as well as a fair share of the profits of their labor. When private capital fails to provide for the common defense and promote the general welfare, it is the obligation of democratic government to intervene, it is the duty of free citizens to resist.

The present economic disorder is destroying the earth. The enduring issue raised at Homestead is “What is the future of work and who gets to decide?”

Will that question be answered by democracy or dictatorship?

Will the future of work be imposed from above by concentrated wealth and power, or by concerted activity from below infused with the dream of a better world?

— Charles McCollester, Ph.D. Former president of Battle of Homestead Foundation and Pennsylvania Labor History Society; Chief Steward UE Local 610; Professor of industrial Labor Relations; Director of the Pennsylvania Center for the Study of Labor Relations, IUP (retired).